Ethics of Bag Limits and Self-Imposed Limits

Should you shoot a limit of wild game birds this season?

During my childhood in southern New Hampshire, kids competed to shoot a limit of “pa’tridge,” my brother and myself included. I admit, I lost just about every time to my older brother. However, we thought shooting the limit was a good idea. After all, it was the 80s.

These birds gave an air of boundless existence. Hunting the droves of ruffed grouse in the Berkshires of Massachusetts when our grandfather was setting up a stand seemed almost too easy. We believed the grouse there and in the woods by my father’s house would be there forever.

But we were wrong. We never thought to ask ourselves, should I shoot that limit?

George Bird Evans wrote:

“Too often, it appears necessary to kill game to show that you found it and had the skill to shoot it. A hunter in my home town used to walk up and down Main Street with grouse hanging from his belt.

One minus aspect of shooting is that idiot’s delight, the Limit Syndrome: ‘Everyone had his limit except Bill, who had only one bird to go to fill out.’ This places shooting on the level of a man digging potatoes with a bag of given size, which he feels compelled to fill before he stops. If the law says he may shoot four birds in a day, or five, the potato digger will keep at it as long as birds fly up, with no thought process of his own.”

A fellow grouse hunter introduced me to the concept of self-imposed limits. This hunter was Jay Dowd, a Michigan-based artist, writer, and grouse guide. After our group took two grouse out of one spot, with casual ease, he mentioned, “I’m not hunting that cover again this season.” Needless to say, his statement impacted me profoundly.

It’s been 20 years since I have seen a grouse by my father’s old house. While I heard the drumming of a couple of distant birds on my most recent Berkshires trip, the idea of a grouse being in every bush was gone. Lack of grouse habitat is undoubtedly the overarching theme of the decline in ruffed grouse, but the idea of limiting yourself increases the depth of how we should view the mortality of the birds we love.

Historical Evidence for Game Bird Management Advocacy

“It seems to me what is called for is an exquisite balance between two conflicting needs: the most skeptical scrutiny of all hypotheses that are served up to us and at the same time a great openness to new ideas,” said Carl Sagan. “Obviously those two modes of thought are in some tension. But if you are able to exercise only one of these modes, whichever one it is, you’re in deep trouble.” This legendary scientist’s quote sums up upland game bird management perspectives.

Depending on the room you’re in, you may observe denial regarding the idea that hunting affects game bird populations. There’s a collective delusion that’s fueled behaviors like “Governor’s Hunts” and other body count-based fundraising events.

George Bird Evans, a famous upland writer, was vocal regarding hunting’s impact on declining bird numbers. Evans’ friction points caused a falling out with the West Virginia Division of Natural Resources when he advocated for the changing of bag limits and seasons. He argued that there was a direct correlation to the decline of grouse in the region.

In New England Grouse Shooting, William Harnden Foster recounts the impacts of market hunting on now-extinct game birds including the heath hen and passenger pigeon. Unregulated bag limits, unrestricted seasons, and the devastating effects of capitalism destroyed populations prior to the Lacey Act. Foster credits the adaptability of ruffed grouse as their saving grace from market hunters; hunting them was too difficult to be profitable.

Today, declining habitat connectivity and quality, climate change, and other compelling evidence threatens ruffed grouse populations. The fact that we needed the Lacey Act to save game populations is compelling evidence that hunting, when improperly regulated through seasons and bag limits, has dire consequences on wildlife populations. Evidently, the need for conversations regarding what defines population sustainability in wildlife management becomes more obvious.

In most states, game bird management is an afterthought. Many states cannot identify how many wild bird hunters there are because they don’t offer a specific license. Some bag limits and season dates have not been adjusted in decades based solely on disinterest of the public and managers.

The days of there being twice as many small game hunters as big game hunters died in the 80s. Game birds no longer have a voice. As a result, they are simply unconsidered. .

Bag Limits Are Not Created Equally

The lack of quality habitat in New England makes grouse very vulnerable. When my brother and I were young, we watched grouse flush and land. You could follow up again and again. We were neither smart nor old enough to understand that the fact we could do this was a symptom of poor grouse habitat.

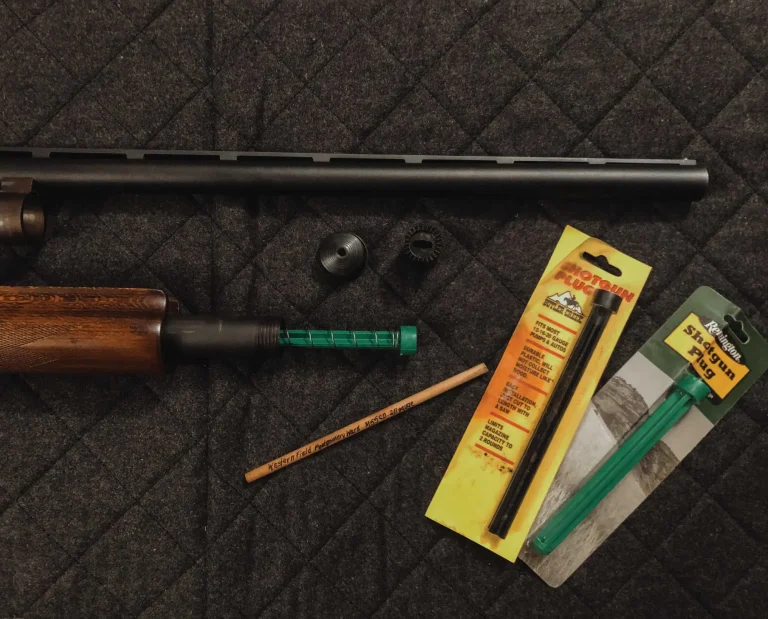

In New Hampshire’s lake region, the daily bag limit for ruffed grouse is four. When I hunt the north country’s expansive grouse country, the bag limit is the same, despite there being more birds than in the lake region. If I hunt the highly-developed Massachusetts border, the bag limit is still four birds.

When I hunt my lake region haunts, Burton Spiller’s very covers, grouse contacts are geographically isolated. Birds hide in small, fragmented forest pockets that are often 10 to 20 square acres with no other cover for miles. What would happen if I took four birds out of one fragment on a single hunt? If I hunted it multiple times over New Hampshire’s 92-day grouse season? If I took just one bird from that cover? Because of what I think would happen if I didn’t self-regulate, I often take no more than one bird from a cover all season. I still run the dog and enjoy the birds, but that’s it. I want to continue to enjoy the birds there. I need to show self-restraint because seasons and bag limits have not evolved with the times.

My thoughts and patterns on this subject are those of someone who has grown up in New England grouse country. But the issue of self-regulation is not unique to the northeast. Even species’ behaviors can change hunting impacts, particularly covey birds, that need a minimum number of birds in a covey to survive the winter.

Tyler Webster of Birds, Booze, and Buds Podcast pointed out the very conservative limits of North Dakota being something to celebrate. They have a Hungarian partridge bag limit of three. Meanwhile, the neighboring state of Montana allows an 8-bird daily limit. Webster points out how that limit can be devastating when hunters pursue a single covey for follow up flushes.

Robert Poor of Arizona pointed out an interesting perspective of bag limits as they relate to desert quail. “The limit on Scalies and Gambels has been 15, an unobtainable number most years. There’s some psychological factors here. If the limit were cut in half for example: who had taken five birds, they may be more tempted to get three more to ‘limit out.’ But with the bar at 15, they are more likely to go home and watch a football game.” This psychology exposes how self-aware we need to be as wild bird hunters.

Since bag limits are not created equally, we need to remember that many state agencies have not evolved with the times or the science. Since these agencies are slow to adjust with the times, the rise in the popularity of upland hunting can have severe consequences. This also speaks to the importance of upland bird hunters’ involvement in state level decision-making. If you do not speak up, no one will.

Bird Hunting Season Dates Can Be Deadly

If you’ve heard of “pickin’ limb fruit,” you may be from New England. This cultural phenomenon points to the vulnerability of game birds based on the time of year.

Ruffed grouse, in this case, are vulnerable when feeding on buds on mature trees while conditions allow for snow roosting. This also means it’s snowmobile season. One can bag multiple limits of birds using a coordinated approach on a tree with friends. It turns my stomach thinking about it, but it happens every season. Is this hunting method sustainable when a bird is a species of conservation concern? There is not a native upland game bird that does not have a listing as a species of conservation concern in 2022.

Late ruffed grouse seasons can also be deadly. Say you’re chasing a ruffed grouse in New York in January. Although the bird may have gotten away, did you mark its death warrant anyways?

The familiar debate here is that the bird expends more energy and burns more calories when being pursued versus their regular ability to survive a hard wintering season with low food.

Western states have shown leadership in this regard. Washington moved their forest grouse season back 15 days to curb breeding hen harvest, therefore raising overall long-term populations. A study published in 2021 showed the impacts on season dates for hunting of sage grouse over 150 years and the direct impact on long term sage grouse sustainability. The study particularly highlighted state responses to the decline of numbers and impact of hunters.

Upland game birds are not a hunting priority in 2022. This led to season dates that have not evolved with the times. Habitat loss exasperates the impacts of a lack of evolution in season dates on upland birds.

Weather Conditions Can Be the Deadliest of All for Birds

Drought, low food crops, and low hatch rates are all factors that can have direct impacts on upland game bird numbers in a single year. Learning how weather and conditions can impact wild birds in your neck of the woods can take a lot of experience and learning the science and biology of your quarry takes time. Even despite our best informed guesses, boot leather confirms our theories.

During New Hampshire’s 2021 season, I heard many grouse hunters complain that they could not find birds and “numbers were low.” The true version of that story is that food crop numbers were down. There was no mountain ash to be found. Highbush cranberry was non-existent. These are often staples to rely on for grouse hunters that stick to the same covers again and again. It took me a couple days to figure out that they had moved into slightly more mature cover, feasting on tree buds at higher rates in the early season to make up for the lack of mast. I had a great season, but tempered my bag limits in covers with the subconscious reminder that food desperation can become more deadly after hunting season.

In the 2018 season, we saw drought. Again, “numbers were low” was the mumbling of those unwilling to put in the boot leather to figure out the complex and rewarding intricacies of grouse behavior. For those of us that targeted water, we found large numbers, but to the point of vulnerability in isolated pockets. This was a great time to exercise self-imposed bag limits on wild birds.

Robert Poor pointed out a very important fact to changing conditions and state regulation. “I used to be in favor of dropping bird limits on poor years. But that would be near impossible to push and respond correctly to population numbers.” This only furthers the argument that a personal ethic when approaching game bird bag limits is something we should consciously uphold.

Bird Limit Ethics in Practice

This article is not meant to chastise those that shoot limits; I shoot limits in the north country. In central New England, I may only shoot one or two birds out of a cover in a season. However, I always consider the population status, conditions, and habitat to support the annual amount of birds and remain aware that this can change season to season.

There are other considerations, too. Traveling hunters might find a greater urge to limit out while being a guest on someone else’s turf. At a minimum, we should consider learning the factors of foreign pursuits and weigh them against our expectations. While hunting North Dakota in 2021, I limited out multiple days over various covers. Tyler Webster, being very aware of our impacts on the spot we hunted, added important local knowledge to making that judgment call.

Comparatively, I remember shooting a sage grouse years ago. The bomber was as tall as me when I spread its wings. Then, I went back to hunting sharptails, declaring to myself, “The next time I shoot a sage grouse will be when I have my dog with me, and it can wait until then.” I made it into fajitas the next day.

Time is another consideration. While I conveniently created a work environment that allows me to hunt as many days as I want in a season, not everyone has that luxury. I even moved to grouse country to have the ability to walk out my doorstep and find wild birds. Truthfully, my impact can be far higher as a result when you add those factors up. My personal ethics must consider that. Similarly, one may take limits when they only have one weekend a year to enjoy wild bird hunting.

These are things guides often consider no matter where they work. Client after client can equate to a lot of bagged birds. Without sound judgment, this can spell disaster to their very own job security. It brings up the debate of guiding on public lands, but I won’t go down that rabbit hole today.

Get your mental wheels turning the next time you drop your tailgate and put your dogs down. There are many iterations of the questions we should all ask ourselves before we fill a game bag. Just because you can do something, should you? This is an intersection of legality and personal ethics because of the slow, ineffective pace our state bag limits and season regulations are created and enforced.

I often self-reflect on the ethics of hunting. I find myself questioning many things the older I get; I am sure this is a natural evolution. I think about how much commitment we make as a community to fight the decline of wild birds, how we put partisan politics aside for the advancement of habitat creation. I think about Project Upland’s role in highlighting species in regions of the country that struggle and our role in the discussion of ethics when new hunters flood our ranks without experienced mentors. We owe it to the birds to question our ethics, challenge our culture to evolve, and be beholden to the science informing game birds’ futures.

George Bird Evans is a wonderful inspiration when considering self-imposed limits in bird hunting:

“If I could shoot a game bird and still not hurt it, the way I can take a trout on a fly and release it, I doubt if I would kill another one. This is a strange statement coming from a man whose life is dedicated to shooting and gun dogs. For me, there is almost no moment more sublime than when I pull the trigger and see a grouse fall. Yet, as the bird is retrieved I feel a sense of remorse for taking a courageous life…

How then, can you love a bird and kill it and still feel decent? I think the answer is, to be worthy of your game. Which boils down to a gentleman’s agreement between you and the bird, never forgetting that it is the bird that has everything to lose. It consists of things you feel and do, not because someone is looking or because the law says you may or must not, but because you feel that this is the honorable way to do it.”